Local Boy Makes Good: Red Scribe John Logan on the Joy of His Tony-Nominated Debut

About the author:

Though his Tony-nominated drama Red is playwright John Logan’s Broadway debut, the two-time Oscar-nominated screenwriter is not a theatrical newbie. The self-proclaimed stage junkie spent 10 years writing plays (notably Never the Sinner, about Leopold and Loeb) before hitting Hollywood with a string of screenwriting successes, including Any Given Sunday, Gladiator (for which he received an Oscar nomination), Star Trek: Nemesis, The Last Samurai, The Aviator (garnering a second Oscar nom), Sweeney Todd and more. Here, Logan reveals his lifelong love of Broadway, where Red came from and how he’s living the dream.![]()

I had a profoundly emotional moment a few months ago when I walked up to the Golden Theatre, looked at the marquee of Red for the first time and saw my name. I grew up in New Jersey, and when I was 12, I began taking the train to Manhattan every weekend, going to the TKTS booth and seeing shows. That was my youth, every weekend I could afford it. I’m a writer today because of all that theater. So for me, having Red open on Broadway is a lifetime dream come true. (Now I like to imagine other kids from New Jersey coming over to see my play.)

The idea for Red occurred to me when I was in London working on the screenplay of Sweeney Todd. I’m a big walker, and I walked around London a lot, but for some reason I would always end up at the Tate Modern museum. At that point, Rothko’s Seagrams murals were on display there. I walked into that room, saw those paintings, and they just stopped my heart. I became obsessed with them.

The murals had a powerful effect on me. They moved me as much as music or a great play moves me. Something about them just connected. The abstraction allows the viewer to bring himself into the work. In fact, the abstraction demands that the viewer bring himself into the work—like a play. A play doesn't just explode all over the audience, nor does the audience simply come to the play. It all happens somewhere in the middle; the audience must meet the play halfway. That relationship reminds me of Rothko's pictures: the viewer must work with the painting. Together they create the art.

I began by doing a bucketload of research. I started learning about Mark Rothko himself. I read everything I could that he had written. Rothko's essays are very dense and challenging, so just hacking through those took me a few months of diligent, banging-my-head-against-the-wall work. Little by little, a Rothko character started coming into focus for me. Then I studied other painters from the Abstract Expressionist School in New York in the 1950s, trying to figure out where he fit in. I realized that wasn’t nearly enough, so I interviewed painters and went to their studios to soak up the reality of what it means to be an artist. The details of the process became important to me, and I thought they would be theatrical on stage. I got the paint under my fingernails, so to speak. I tried to internalize as much research as I could, then I just forgot about it and wrote the play.

Despite all the research, Red is not a work of reportage. It’s a work of drama, not history. It is not meant to represent a complete biographical portrait of Mark Rothko. I tried to stay true to the spirit of the man, at least as I interpret him. I never wanted to write a play where big “thinky” people sit around and talk about art. Instead, I want to write something where two vital and passionate men are actively engaged and constantly working. I always imagined it as a two-hander because that somehow reflects the feel of the paintings. There’s dark and light, interacting, and from that duality came the idea of two actors: a young man, an old man; a teacher, a student; a protégé, a mentor. To me, at its heart, this has always been a domestic play, a father-son story.

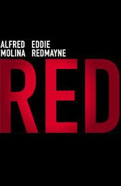

I’m having the playwright’s dream right now. I wrote a play because it moved me. I gave it to Michael Grandage, the director I thought would do it best in the world. I got to do it with two extraordinary actors, Fred Molina and Eddie Redmayne, who are powerfully committed to the work. Finally, it came to Broadway—my Broadway debut after all those weekends when I was a kid! I can't imagine anything more thrilling… except the next play.